https://parabola.org/2019/04/28/the-courageous-mary-oliver-by-lisa-starr/?fbclid=IwAR3-ARQCnFSX5dozryfQOKgRpDYc-dIAywJiyFiaZ-Ij1JyEwdtRpoey37M

The Courageous Mary Oliver, by Lisa Starr

Photographs by Tricia Spoto

I will be forever grateful to Coleman Barks for many things, but there is no doubt that his greatest gift to me was introducing me to his friend, my hero, the poet Mary Oliver. As the first raw days since her death have stretched into two months, I am learning that it is nearly impossible to name my love for her, nor my awe for how she lived her life and what she accomplished with it. So since I can’t quite name the grief nor the wonder, nor my sadness for the honey locust tree, the grasshopper, the red fox and the sun in the morning, now that she is no longer here to celebrate their beauty—what I’ll do is tell you a little about the Mary Oliver who was my friend.

Mary

was private, humble, fierce, intuitive, and hilarious. She made funny jokes and

faces; she didn’t miss a beat; she kept a secret stash of cash in her desk in case anyone she knew got into some trouble and needed quiet help. On the

envelope were the words “floating money.” Mary loved the everyday people—the

ones who delivered letters to her mailbox and brought her clams they’d just dug

up from the sand. And though she lived reclusively, she always

found out who “her people” were, and found a way to help them. There are

families whose rent she paid; a young girl who needed braces for her teeth, a

friend, down on his luck, who needed a car and a place to stay. And while Mary’s generosity to others is its own legacy, what I want to

emphasize here is her strength, for more than anything, Mary Oliver was

courageous.

We

now know, through some of the later poems, a few of the details about the abuse

she endured as a child, and we also know that she used

her craft to transform not only her own suffering, but also the heartbreaking

nature of the world—the fact, say, that everything and everyone is going to

die—into a thing of beauty. Think of “Night and The River;” think of the snapping turtle she found and captured in the city and released

into a nearby pond because: Nothing’s

important/except that the great and cruel mystery of the world,/of which this

is a part,/ not be denied.

Mary

was one of the greatest teachers about death and grief that we will ever

know because she was one of their finest students. And though the courage to

not look away is everywhere in the poems, I couldn’t possibly know the true

depth of Mary Oliver’s courage until these last few years as she battled a series of cancers, each more aggressive than the last. There is

no need to go into the list of diseases, treatments, hospitalizations, and

indignities. I won’t talk about the hours in the chemo unit, the cheerless fish

tanks, or the despair Mary felt about the “chemo brain” that was

barring her access to language.

What I will tell you about is her resilience. Her faded blue jeans and Carhartt jacket and bright argyle socks. I will tell you how she’d wink at me from across the waiting room. How she’d tell me not to get too sad. Let’s not go there just yet, she said one day when she caught me crying on the drive home from the hospital. I want to tell you about how she handled the news of the feeding tube and I really want to tell you what she said the day she decided to refuse all further treatments and let the lymphoma run its course, but when I do, the words get replaced by tears, so I will tell you instead about the wild geese as they circle and land in the field just across the street from where I sit writing these very words, right now.

They’ve

been doing it every day since I’ve been home. By home, I mean from Hobe Sound,

Florida, where I had the honor of being with Mary for the last week of her

life. A small team of friends shared the privilege of washing

her hair, holding her, singing to her, and reading her own amazing poems to

her. We played some rock and roll when we needed to. Lots of coffee. Lots of

cookies. Lots of tears.

In the days following Mary’s death, as we slowly tidied up the bedroom and tried to get used to the startling absence of her tiny body, surely we each took our own inventory of that spare room where she slept and worked for the last three years of her life—the work table and the typewriter, the twin bed and the night stand with her well-worn copy of A Year With Rumi, and the small yellow legal pad on which she wrote the words and phrases that still came, though to her great dismay, with less and less frequency. They don’t come around much, she said, but when they do I always let them in.

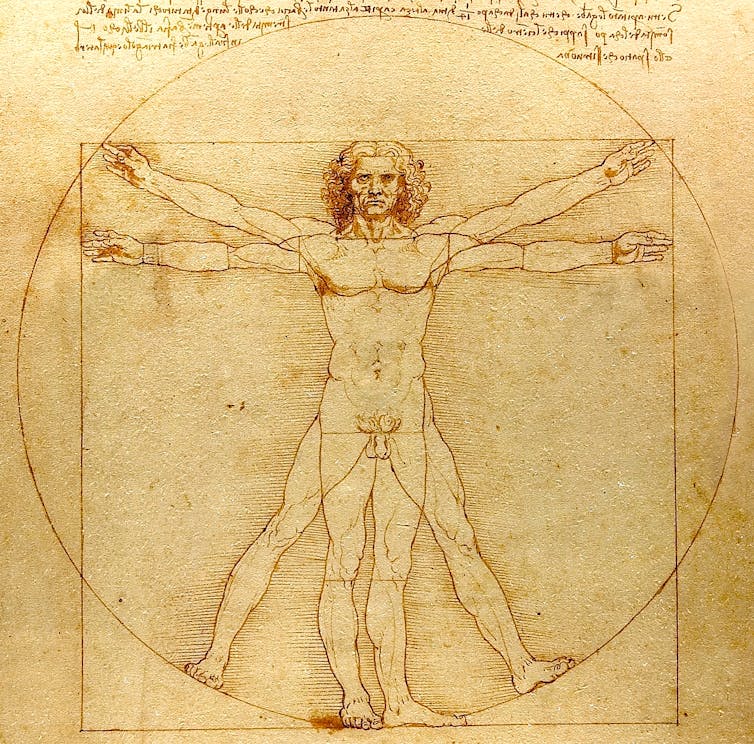

Mary Oliver (r) and Coleman Barks (l.)

The

space is quite monk-like—half the size of a college dorm room. On her desk a

tidy stack of books, a bowl of special stones from Provincetown, and a few

photographs of her favorite people. On the top shelf I found the Sufi begging

bowl Coleman gave her a few years ago. It’s a

beauty—dates back some eight hundred years—brass with dragons’ heads on either

end. She loved it; cupped it in her hands and rubbed it against her face when

he gave it to her. Two days after Mary died, when I picked it up to rub it against my face the way she had, I noticed it was filled

with several coveted talismans (a whale bone, a bluebird feather, an arrowhead)

and a few dozen small strips of paper that looked like confetti. As I pulled a

few of them from the bowl I discovered that they each had a

quote from Rumi.

Those

who knew Mary well know that she continued to use a typewriter up until the

very last of her writing days, and they also know she started each day reading

a passage from Rumi as an invitation for her own

words to come back. I think now of her process. I think of her putting the

paper into the typewriter, adjusting it to the right height and then typing a

line she loved. Then another, and then another until the page was filled. And

then I see her pulling the paper from the typewriter and

with great focus cutting the lines into neat little slips of paper and putting

them in her begging bowl.

Day

after day after day, she pulled one out and thought about it, and hoped the

words would come. Astonishing enough—the intention and the discipline.

But what strikes me now is her fearless determination to keep finding the new

thought, to find the words that said the world a little better, the ones that

saved my life, and yours. All of this in the last three years of her life, when language was leaving her. Despite the anguish that it

brought her to see the words slip a little further away daily, she never gave

up. And the thing is, it was an act of love for each of us, for she didn’t need

her poems nearly as much as we do.

Now, back to the geese….I don’t mean one flock. I mean that dozens of flocks of wild geese have been barreling in from all directions for more than a month now. It’s like Woodstock out there—a crowded clamor of geese that circle, usually, right above the roof of my condo before turning back and landing on the field I overlook. There are thousands of them out there now, with more coming in. I can see them in the distance, some coming, some going, some in V-formation, others like a long, faint, scribbled pencil mark across the sky, like the one, in fact, on the small yellow legal pad on the table right near Mary’s bed. Surely I don’t need to tell you that as they come and go, each one of them calls her name. ♦

From Parabola Volume 44, No. 2, “The Wild,” Summer 2019. This issue is available to purchase here. If you have enjoyed this piece, consider subscribing. Four times a year Parabola has explored the deepest questions of human existence. Without your support, we would cease to exist. Please consider helping us by making a donation.